Drinkers who glance down between sips may eventually read the fine print on any bottle of booze warning about its hazards. But critics say there’s a huge oversight when it comes to labeling: no mention of the link to cancer.

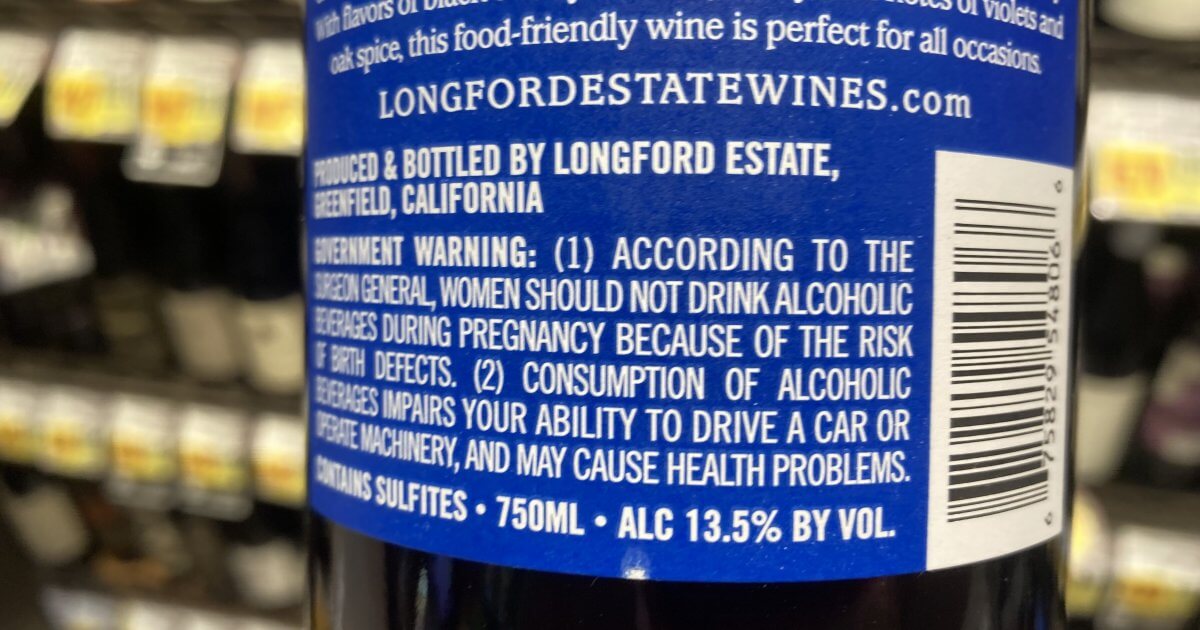

While the label language on any can or bottle, from chablis to scotch, covers the harm that can come from imbibing during pregnancy and from drunken driving, advocates think there’s ample evidence that cancer should be there as well.

Read MoreResearch on Alcohol & Cancer

The petition states there is ample evidence connecting drinking to cancer. Among the studies it cites is one published in 2017 that estimates 5.6% of cancer cases and 4% of cancer deaths in the U.S. could be attributed to drinking. Among the risk factors over which individuals have a choice to control, alcohol consumption was only behind smoking and obesity as causes.

There’s been more evidence since the petition was submitted in October.

The study takes a worldwide perspective. Published in The Lancet, an oncology journal, it estimates that 4.1% of new cancer cases globally in 2020, more than 700,000 in total, were due to alcohol intake. About three out of four occurred in men and some 46% overall involved heavy drinkers. But even light drinkers, those who consumed less than a single drink a day, were found to be contracting cancer.

"Our findings highlight the need for effective policy and interventions to increase awareness of cancer risks associated with alcohol use and decrease overall alcohol consumption to prevent the burden of alcohol-attributable cancers," the researchers wrote.

The cancers included those in the mouth, esophagus, stomach, rectum, liver and breast.

Any effort to add cancer to container warnings could run into opposition from alcohol beverage industry organizations. A major one, the Distilled Spirits Council, acknowledges the latest study in the Lancet, but points to its author’s acknowledgment of limitations, such as whether tobacco use in addition to drinking may have clouded the results. The council notes its longstanding policy of urging moderation when it comes to drinking.

The petition was submitted to the U.S. government agency charged with enforcing the current labeling rule.

"We did receive that. We are looking into that," confirms Tom Hogue, spokesman for the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, a Treasury Department unit that reviews labels on cigarette packages and alcohol containers, among many tasks, to make sure their warning labels meet the requirements of the law. It's burdensome: the bureau receives about 200,000 label applications a year.

Increasing Public Awareness

But it would likely take an act of Congress to make the change for alcohol beverage containers, just as it did to create the requirement in the first place. The current label warning dates to 1988 when it passed Congress with the late Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-S.C., as its primary sponsor.

The required warning urges pregnant women not to drink "because of the risk of birth defects" and says driving or operating machinery after consuming alcohol can be dangerous. As a vague parting catchall, it cautions alcohol "may cause health problems."

The time has come to add cancer to the label because there is so low public awareness of the effect that alcohol can have, said Thomas Gremillion, director of food policy for the Consumer Federation of America.

"We have optimism that Congress and the agencies will come along on this," Gremillion said.

The U.S. isn’t alone in trying to decide how to deal with the issue. Other countries have weighed alcohol warning labels when it comes to cancer. A proposal is before the European Commission. As submitted in February, there may be action by the end of the year.

The Potential for Backlash

But warning imbibers about their cancer risk can provoke a backlash. A warning label program was briefly tried in the Yukon, the rugged, lightly populated northwest Canadian province known for a preponderance of heavy drinkers. Four years of planning went into the test and it took only 30 days before it was hastily canceled after an outcry.

Objections ranged from allegations that the warning defamed brands to an outright rejection of the message, arguing there's no solid proof alcohol consumption leads to cancer, said Dr. Tim Stockwell, a scientist at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research.

Every one of the claims was "nonsense," insists Stockwell. But he said the government caved to industry pressure and stopped the project.

He said success would have required more leadership to stand up to the pressure. There was no doubt about the need to get the word out: "The more you drink, the more you need to see the message," said Stockwell, who is also a psychology professor at the University of Victoria.

The U.S. faces other barriers to a label change as well. Many consumers view alcohol as having health benefits, that a glass or two of red wine can help prevent heart disease.

Cancer experts understand the confusion and as a result, are divided.

Cancer warning labels could help, but consumers nowadays are flooded with so many red flags that it’s easy for them to be overwhelmed, said Dr. Dawn Severson, an oncologist for the Henry Ford Cancer Institute in Michigan.

“The ubiquity of warnings in society tends to lessen their impact,” said Severson, who has written on the relationship between cancer and alcohol.

Dr. Elizabeth Comen, an oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, said messaging brings awareness, which is good, but wonders, too, whether consumers are paying attention. Tobacco packages have lots of warnings, she notes, but it’s unclear whether it is dissuading smokers from lighting up.

And Dr. Adrienne Phillips, an oncologist who teaches at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, acknowledges messaging on alcohol and health can be confusing. But one thing she and the others agree on is that less alcohol is always better when it comes to warding off cancer.

“As with many things in life, anything in excess is likely bad for you and the less alcohol you drink, the better,” Phillips said.

Severson goes a step further and says cancer survivors should abstain completely from alcohol.

Experts also recommend that all patients talk to their doctor if they have any questions about how much is too much when it comes to alcohol.

Dr. Stacie Stephenson, a doctor of chiropractic who is founder and CEO of the health and wellness media venture, VibrantDoc, and chair of Functional Medicine at Cancer Treatment Centers of America, said she is careful to caution patients when it comes to accepting or rejecting health claims involving alcohol. A lot depends on age, gender, lifestyle and genetics.

"Health," she said, "is highly individual."

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.