Promoting Hope and Raising Awareness for Cervical Cancer

- Actress Pam Grier, 74, was diagnosed with stage 4 cervical cancer in 1988. Despite being told she had only 18 months to live, her cancer treatment, which included surgery and chemotherapy, proved effective in helping the resilient “Miami Vice” actress to thrive to the present day.

- Cervical cancer begins in the cells lining the cervix, the lower part of the womb (uterus). It usually develops slowly, however, before cancer presents itself. Vaginal bleeding or pelvic pains are common symptoms.

- More than 70% of cases of cervical cancer are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). More than 90% of HPV-related cancers, including cervical cancer, are preventable in people who get the HPV vaccine that is recommended for all preteens (both girls and boys) 11 to 12 years old.

- The human papillomavirus, or HPV, is a group of more than 200 related viruses, some of which are spread through vaginal, anal, or oral sex, according to the National Cancer Institute. It can cause a handful of cancers, including cervical and throat cancers.

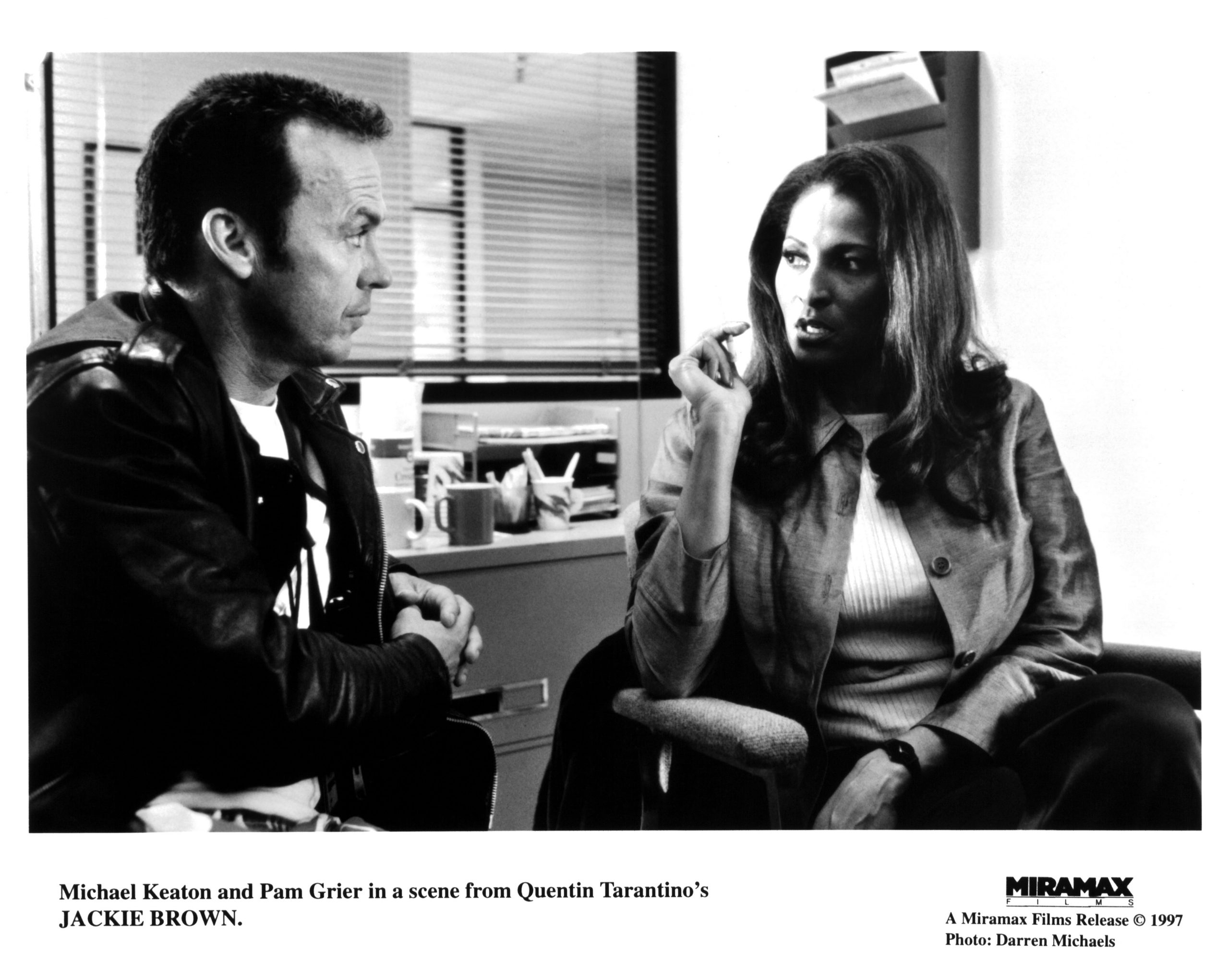

“Miami Vice” actress Pam Grier, 74, was diagnosed with stage 4 cervical cancer more than 35 years ago, and she’s still thriving. She now holds an honorary doctorate and is basking in the limelight yet again as one of her films, “Jackie Brown,” was among Netflix’s 25 Best Movies to Stream. In honor of Cervical Cancer Awareness Month, SurvivorNet is shining a light on Grier’s cancer journey to provide added hope to other women battling the disease.

Grier, known for her roles in “Foxy Brown,” “Miami Vice,” “The Big Doll House,” and “Coffy,” is an award-winning actress whose career has spanned decades. At the height of her success, she was forced to deal with a setback when she was diagnosed with cervical cancer. This type of cancer begins in the cells lining the cervix, the lower part of the womb (uterus). Treatment options for cervical cancer include surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

Read More

She described her treatment as a “full-time job,” which included chemotherapy.

“In 1988, the C-word meant: ‘Oh my God, you’re going to die. There is no hope. ‘You learn who your friends are when you have cancer.”

Thankfully, Grier’s treatment worked, and she was able to reach remission and continues to thrive 36 years after her stage 4 diagnosis. She considers herself lucky.

Helping Patients Understand Cervical Cancer and Its Link to HPV

- ‘Controversial’ HPV Vaccine Shown to be Highly Effective in Wiping Out Cervical Cancer

- Can the U.S. Eliminate Cervical Cancer? Australia Says It’s About to Do Just That

- Farewell to the Pap Smear? World Health Organization Recommends HPV DNA Test As Best Screening Option for Cervical Cancer

- Breaking: HPV Vaccine Not Recommended For Adults Over 26, Per New American Cancer Society Guidelines

- Busting the Myths About the HPV Vaccine

- Cancer Doctor Explains Why Her Young Kids Are Getting the HPV Vaccine

Helping You Better Understand Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer forms in the cells of the cervix, the lower, narrow end of the uterus (womb), which connects the uterus to the vagina, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

“Cervical cancer usually develops slowly over time. Before cancer appears in the cervix, the cells of the cervix go through changes known as dysplasia, in which abnormal cells begin to appear in the cervical tissue,” the NCI explains.

“Over time, if not destroyed or removed, the abnormal cells may become cancer cells and start to grow and spread more deeply into the cervix and surrounding areas.”

While symptoms tend to be difficult to detect during cervical cancer’s early stages, some signs can still indicate something is amiss and needs a closer look.

The NCI explains that symptoms of early-stage cervical cancer may include:

- vaginal bleeding after sex

- vaginal bleeding after menopause

- vaginal bleeding between periods or periods that are heavier or longer than normal

- vaginal discharge that is watery and has a strong odor or that contains blood

- pelvic pain or pain during sex

A Common Cause

Cervical cancer starts in the cervix, and more than 70% of cases are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). More than 90% of HPV-related cancers, including cervical cancer, are preventable in people who get the HPV vaccine that is recommended for all preteens (both girls and boys) 11 to 12 years old in two doses administered between six and 12 months apart. The shots can also be started as early as nine years old.

“The key with the vaccine is that you received the vaccine before you ever reach sexual debut or have sexual encounters. So that’s why these vaccines are approved for young children ages 9, 10, 11 years old, up to 26,” Dr. Jessica Geiger, a medical oncologist at Cleveland Clinic Cancer, told SurvivorNet.

The American Cancer Society recommends cervical cancer screenings begin at age 25, and HPV screening is recommended every five years after that.

Understanding HPV

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is “a group of more than 200 related viruses, some of which are spread through vaginal, anal or oral sex,” the National Cancer Institute says.

HPV infection is linked to multiple cancers, and the majority of sexually active people will get the disease at some point in their lives.

Although nearly all cases of cervical cancer are indeed caused by HPV, people should also be aware that HPV puts both men and women at risk of developing several other cancers, such as oral cancer and cancers of the vagina, penis, anus, and throat.

Overall, HPV is believed to be the cause of 90% of anal and cervical cancers, approximately 70% of vaginal and vulvar cancers, and 60% of penile cancers.

“There are no screening guidelines to screen for throat cancer, unlike cervical cancer with pap smears,” says Dr. Jessica Geiger, a medical oncologist at Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center, previously told SurvivorNet. “There are no standard tests to determine if you harbor the virus.”

On the plus side, HPV-related throat cancers are generally very responsive to a combination of radiation and chemotherapy treatments, according to Dr. Geiger.

“The cure rates for people who have HPV-related disease are a lot higher than those who have tobacco-related throat cancer,” she said.

WATCH: HPV’s link to cancer.

Protecting Against HPV

Nearly 80 million Americans have HPV today, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It impacts men and women and won’t cause problems for most people.

However, in a small percentage of cases, it can lead to cancer.

The HPV vaccine is recommended to protect against HPV and, therefore, HPV-related cancers.

Gardasil 9 is an HPV vaccine that offers protection against “nine HPV types: the two low-risk HPV types that cause most genital warts, plus seven high-risk HPV types that cause most HPV-related cancer,” according to the National Cancer Institute.

The vaccine creates an immune response to HPV 16, the primary cause of 92% of head and neck cancers. Once children are vaccinated, they cannot be infected with that strain. For parents, the HPV vaccine enables them to protect their children from developing cancer in the future.

“The key with the vaccine is that you receive it before you have sexual encounters,” says Dr. Geiger. “So that’s why these vaccines are approved for young children … ages 9, 10, 11 years old, up to age 26.”

The HPV vaccine is recommended for all male and female preteens 11 to 12 years old in two doses given between six and 12 months, according to the CDC.

The series of shots can also start as young as nine.

The CDC also notes that teens and young adults through age 26 who didn’t start or finish the HPV vaccine series also need the vaccine.

Additionally, people with weakened immune systems or teens and young adults between 15 and 26 who started the series should get three doses instead of two.

Although adults up to 45 can still receive the vaccine, it’s not recommended for everyone older than 26. Still, a person older than 26 could choose to get vaccinated after talking to their doctor about possible benefits, even despite it being less effective in this age range, as more people have already been exposed to HPV by this point.

WATCH: Should children get the HPV Vaccine?

Vaccine hesitancy can impede people from getting the vaccine. The concern may come from parents who may feel the vaccine paves the way for early sexual activity. For this reason, some health practitioners are educating the public about the vaccine differently.

“I think rebranding the vaccine as a cancer vaccine, rather than an STD vaccine, is critically important,” says Dr. Ted Teknos, a head and neck cancer surgeon and scientific director of University Hospital’s Seidman Cancer Center.

Dr. Teknos believes concerted efforts to “change the mindset around the vaccine” can make a difference.

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.