James Patterson's Prostate Cancer Battle

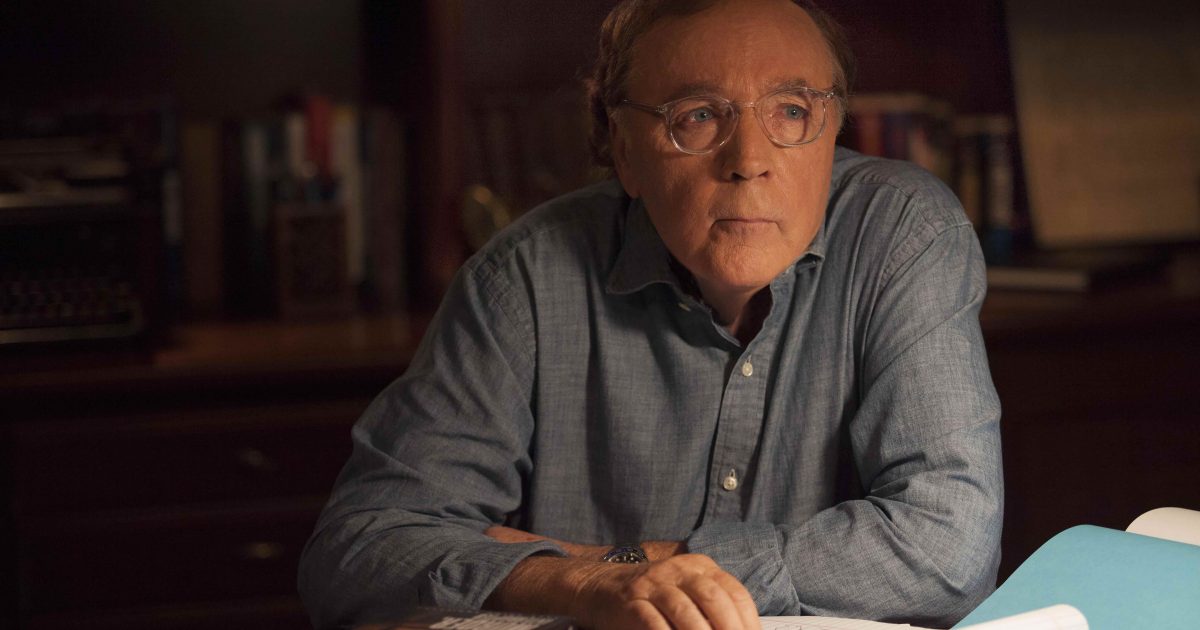

- James Patterson, America’s bestselling author, warns that if he hadn’t been tested for prostate cancer, he wouldn’t be around to write now.

- Risk level for prostate cancer depends on a set of various circumstances that have been mapped out by the American Cancer Society.

- Behaviors surrounding diet, weight, exercise, and smoking all contribute toward increased prostate cancer risk; Patterson emphasizes that above all, getting tested is the most important behavior to focus in on and take control of.

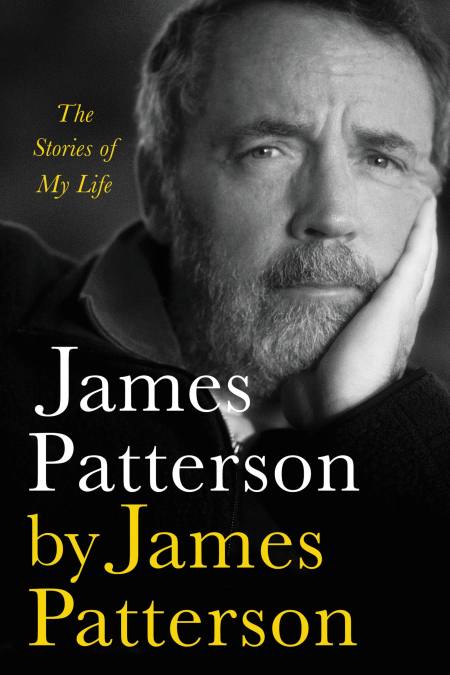

This isn’t Patterson's only personal story of tackling a cancer diagnosis. He addresses how the disease has touched him more than once throughout his life in his new memoir, The Stories of My Life, out in June.

Read More

Patterson, who turned 75 in March, addresses a chapter in his memoir that references times he’s faced "the grim reaper" the first being when he was a baby and almost died. "And I've had some bouts with a couple things prostate surgery, a little lung surgery, so some of that, too."

He adds, "I've always been pretty good about accepting what life throws at me."

View this post on Instagram

Attitude is key, says Patterson. "I tend to be sort of humorous about things, even serious things sometimes. I think humor is one of the best things you can do for yourself."

But he's serious about cancer, and what the future might have been for him and his books if he hadn't taken it seriously.

"A few years back I had prostate surgery at the Mayo Clinic. But if I hadn't been tested, I might not be writing now. No more James Patterson; no more Alex Cross; no more Women's Murder Club, and for me, no more hot fudge sundaes once a month."

Diet. Weight. Exercise. Smoking. All of those behaviors add to the risks. Most important, Patterson says again and again throughout our interview, is testing.

"If you're a male of a certain age, talk to your doctor about getting tested. If you have a loved male in your life, or even a liked one, talk to him about getting tested."

Then he can't help himself. "If you want to kill some guy or at least have him neutered, advise him NOT to talk to his doctor about getting tested," he says, adding, "There's an idea for a nasty mystery novel."

Patterson recalls in 2016 that when he got his PSA report, he was "still in the safe zone."

A PSA test is a blood test that measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in your blood. PSA is a protein produced by both cancerous and noncancerous tissue in the prostate, a small gland that sits below the bladder in males.

Patterson's numbers had increased, he said. And "even though I was still fine," his doctor recommended a biopsy, to be safe. “Yep," Patterson remembers being given options. "We opted to take the prostate out."

Common treatment options for prostate cancer include radiation, surgery, chemotherapy and hormone therapy.

It saddens him to think that people don't get the testing and, if needed, the procedure. "You see these relatively young men dying because they didn't do anything. They didn't deal with it."

The American Cancer Society recommends screening at:

- Age 50 for men who are at average risk of prostate cancer and are expected to live at least 10 more years.

- Age 45 for men at high risk of developing prostate cancer. This includes African Americans and men who have a first-degree relative (father or brother) diagnosed with prostate cancer at an early age (younger than age 65).

- Age 40 for men at even higher risk (those with more than one first-degree relative who had prostate cancer at an early age).

In addition to the PSA test, a Digital Rectal Exam (DRE) may be done as part or the screening.

"I'll tell you a funny story," says the master storyteller, recalling his doctor at Mt. Sinai getting ready to do "put his hand up there" for the prostate screening. "The doctor said, 'Do you mind if I play some music for you, James?' I go, 'Sure, whatever.' Then on comes the music, Strangers in the Night. I said, oh no, no, no. I don't mind music, but I'll never be able to listen to that song in the same way again."

During his time at the Mayo Clinic for surgery to remove his prostate, Patterson befriended a hospital worker who was guiding him through the process. "She had this wonderful name Angela Hoot. I really liked her. I actually used her name in one of my novels." When "1st Case" came out featuring one Angela Hoot as a main character, Patterson says they had a reunion in Minneapolis, and "she cried a little bit."

View this post on Instagram

So, is Patterson now 100%? "I would say I'm 92.5 percent. It's ok. Look, I don't know how much of it is age. I won't be having any babies, but it's OK." (He has one son, Jack, 24, with wife Susan, whom he wed in 1997. Jack is in the banking business.)

The survival rates following a prostatectomy are good:

- 5 years: nearly 99%

- 10 years: 98%

- 15 or more years: 96%

"My doctor says I'm the poster boy for preventive surgery. I had the prostate surgery," he says, then adds, "I had lung surgery. Once again, it was just a spot. Out, out damn spot. Just a spot. Got rid of it."

Patterson says that one "spot" had been in his lungs for four years and it didn't change, until one year his doctor noticed it had changed "a fair mount" from one checkup to the next. "The surgeon a lady who had been operating on Ruth Bader Ginsburg for a decade. I thought I was in good hands, and then she died and I got rid of the surgeon.” He laughs. “No, she's great."

In both cases lung in 2018 and prostate in 2016 he had no treatments after the surgery.

"Neither case I've been fine. I go in once a year to check the lung. It was once every six months, now it's once a year. And then it'll be every two years."

His other experience with cancer came when he was much younger, with Jane, the first love of his life.

"I was 26 we went out for breakfast in New York one Saturday morning, and we stopped at the post office and she just fell over. There happened to be a nurse there and she came over and said, 'I think she's having a seizure.'"

They went in for testing, Patterson says. "She found out that she had a brain tumor, inoperable. They gave her, like, a year and a half. It wound up being two and a half years."

Patterson says, "She was a spectacular person; it was a terrible loss."

He adds, "It was kind of weird, but as a teenager, I could not cry. I remember I was very close to my grandfather and he died. I was in New York just walking through the woods and trying to cry. You know how sometimes you need to throw up but you can't? It was like that. I couldn't cry. When Jane got sick, I cried every day for two years. Since then, I watch the goofiest movie in the world and I'm weeping. It opened up the tear ducts."

While Jane's passing was a "terrifying, terrible thing," he says, "the good thing for me is that it taught me that you can have wonderful love affairs, relationships. We were together for seven years including the time she was sick."

View this post on Instagram

As for what it taught him about cancer? "I don't like it. Negative. I'm biased against cancer. Look, it's clearly a terrible thing to have, or for someone you love."

And he returns to the message and importance of testing.

"I don't tend to shy away from things. I think I'm pretty realistic. I will get go tested, do the rational thing."

But a lot of people won't. A lot of people will say "I don't want to know." To that, Patterson says, "You do want to know. If you don't have anything, 'Yay, I'm great." If you do have something, you want to know as soon as you possibly can. And anyone who doesn't think that is a fool. You're just being foolish. You're putting your life at risk. You're putting your family at risk. You shouldn't do that."

Patterson says he's "not big" on advising people. Even when he taught a master class on writing, he told students, "Look, I'm not giving you advice on how to write, I'm just telling you what I do. That's all."

And with cancer, he says, he realizes it's a scary proposition. "I know what it is: It's either 'I don't want to spend the $100' or whatever the heck, or you don't want to know. People are silly that way. I get it. But you really do want to know. You want to get the good news or you want to get the not-so-good-news as early as you can."

And we're back to where we started. "If I hadn't gotten that news when I did with the prostate," he says, "I wouldn't be here. Period."

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.