Finding Hope In a Bone Marrow Transplant

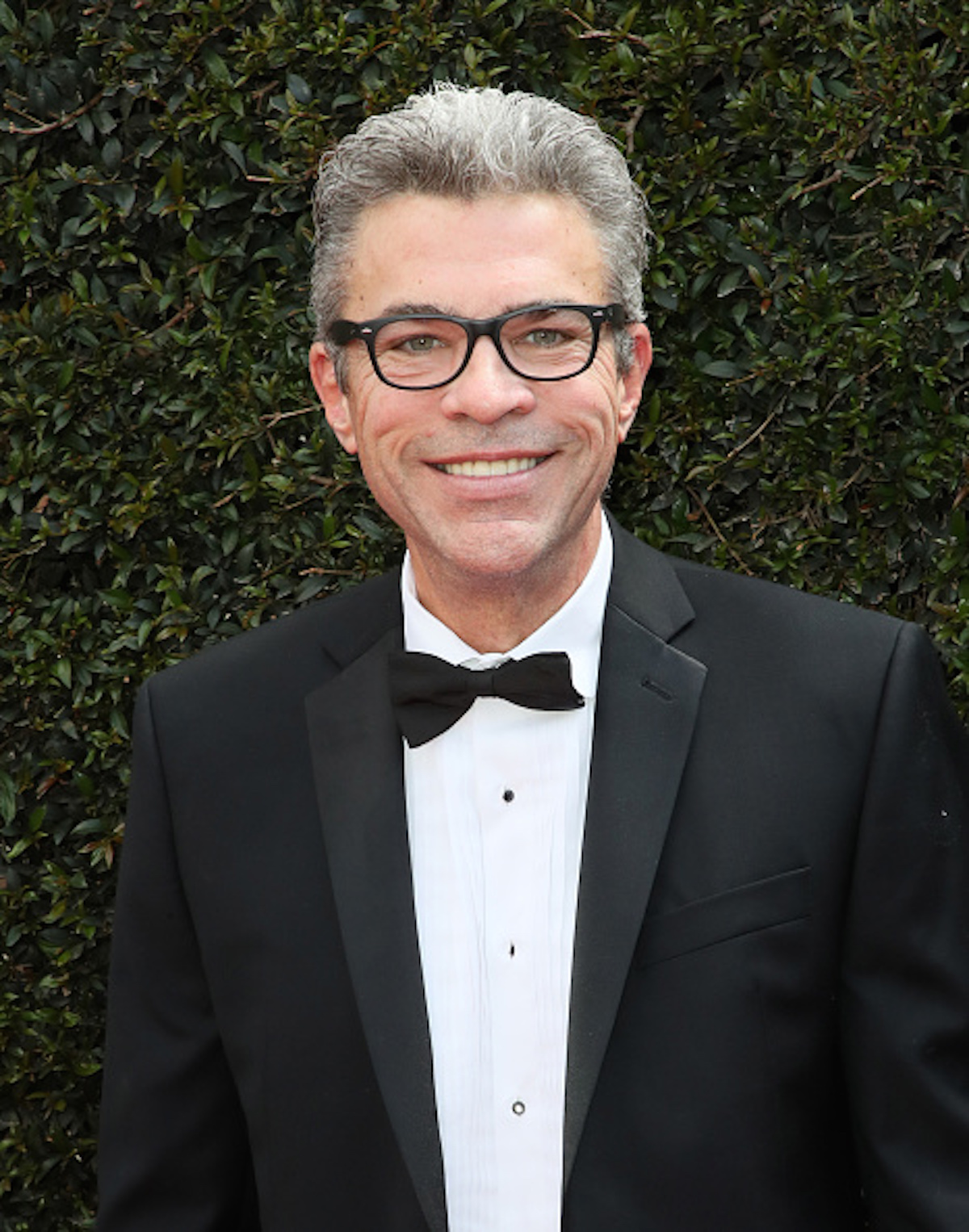

- “General Hospital” star John York, 64, has begun treatment for his blood and bone marrow disorders. He’s undergone blood stem cell transplantation.

- “A bone marrow transplant is a therapy where your bone marrow and your blood cells are completely replaced by someone else’s bone marrow cells and blood cells,” Dr. Jun Choi, a hematologist-oncologist at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, explains to SurvivorNet.

- York was diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and multiple smoldering myeloma.

- MDS is a variety of bone marrow disorders that look similar. Under a microscope, the bone marrow cells look like cancer and, genetically, may have alterations that are known to cause MDS.

- Symptoms of MDS include frequent infections, fatigue, shortness of breath (anemia), or easy bleeding/bruising. These symptoms are the result of the bone marrow not being able to produce enough healthy, functional blood cells.

- Smoldering myeloma is close to becoming active myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells. It is characterized by higher levels of abnormal proteins in the blood and plasma cells that comprise more than 10 percent of the bone marrow. Smoldering myeloma aims to keep it from becoming an active disease.

“General Hospital” star John York, 64, is nearly a year into his cancer journey with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and multiple smoldering myeloma. These blood and bone marrow disorders have led the actor best known for portraying “Malcolm Scorpio” to undergo a blood stem cell transplant for treatment.

“There’s still a long road ahead, but these next 100 days, I would say, is rocky terrain,” York told People Magazine.

“It’s a whole new ballgame,” he said.

“The first week is an 8-day process of heavy-duty chemo, where I’ll probably lose my hair, and that’s okay,” he said.

York added the transplantation will be a stressful experience, which includes intensive chemotherapy and potential side effects that come with it.

“They’re basically wiping my body of what I’ve been living with in terms of my blood and DNA and all this stuff for my entire life. They’re wiping that clean, and then they’ll put new stuff in me from the donor. And that’s going to be the new me,” York said.

“The only curative option [for] MDS these days is a bone marrow transplant,” Dr. Jun Choi, a hematologist/oncologist at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, tells SurvivorNet.

“Now, bone marrow transplant is one of the more intense therapies for MDS, so you really want to be able to tolerate this therapy. That is why this therapy is reserved mostly for younger patients and [those] who do not have other medical conditions,” Dr. Choi adds.

He will have to go to the hospital for 100 days straight and be tested through bone marrow biopsies to monitor the disease.

WATCH: Understanding bone marrow biopsies.

Bone marrow biopsies take samples from the back of the hips by inserting a needle and extracting liquid bone marrow and a small piece of bone for examination. As said, a bone marrow biopsy is often done using the pelvic bone, but another bone (such as the breastbone) may be used. A leg bone or a bone in the spine (vertebra) may be used in children.

The procedure may be performed under local anesthesia, with some anti-anxiety medications to relax you. It usually takes about 15 to 30 minutes, but extra time is needed for preparation and post-procedure care, especially if you receive intravenous sedation. The procedure is often outpatient by a doctor specializing in blood disorders (hematologist) or cancer (oncologist).

Although bone marrow biopsies are necessary for York’s treatment, he admits that the testing involved is “not [his] favorite thing in the world to do.”

“If tests come back after, let’s say, after 30 days or 35, 40 days, tests are looking really good, that would be wonderful. Then they may say, ‘You don’t have to come in tomorrow, come in the next day. And then we’ll test after that.’ That goes on for 100 days, and I would say the first probably 20 days [after the transplant] are the crucial days. From the first day of the transplant, I’m guessing 14 to 20 days out, they’ll be able to tell with testing daily how I’m receiving and accepting the stem cells,” York explained.

Helping Patients With Their MDS Journey

Better Understanding York’s Cancer

Myelodysplastic syndrome is a variety of bone marrow disorders that look like each other, meaning under a microscope, the bone marrow cells look like cancer and genetically may have alterations that are known to cause MDS. Common symptoms of MDS may include frequent infections, fatigue, shortness of breath (anemia), or easy bleeding/bruising. These symptoms occur because of the bone marrow’s inability to produce enough healthy, functional blood cells.

Some patients with MDS will have their cancer evolve into acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Thus, your doctor needs to monitor your risk. They can monitor the risk by looking at your blood counts, the amount of cancer in the bone marrow, and any genetic abnormalities.

“For the workup of MDS, you start with a regular blood check, and you confirm that someone has low blood cells,” Dr. Choi explains. “And then, when the suspicion for MDS is high, the ultimate gold standard diagnostic test is a bone marrow biopsy. And that is because the bone marrow is where all the blood cells are made. And we want to confirm that there are abnormal cells in the bone marrow.”

A bone marrow biopsy can confirm MDS. It can also provide other details on your cancer.

Treating MDS

MDS patients’ treatment options depend on symptoms and the risk for it to evolve into AML.

For lower-risk MDS:

- Many people may only need to monitor blood counts every few months without specific treatment.

- Some people may be started on medications to stimulate RBC or platelet production.

- Some people may need a blood transfusion every few months.

- Specific types of MDS may benefit from lenalidomide (Revlimid), luspatercept (Reblozyl), or immunosuppressing medications.

For higher-risk MDS:

- Treatment usually starts with a class of drugs known as hypomethylating agents (HMAs). HMAs include intravenous or oral forms of azacitidine (Vidayza, Onureg) or decitabine (Dacogen, Inqovi).

- Other treatments are possible depending on the presence of certain mutations or if the disease is more aggressive.

- Some patients may require more frequent transfusions, from every few weeks to even several times a week.

- Some patients may be eligible for a bone marrow transplant.

- Many patients should consider enrolling in a clinical trial if available.

Understanding Smoldering Myeloma

Smoldering myeloma is close to becoming active myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells. It is characterized by higher levels of abnormal proteins in the blood and plasma cells that comprise more than 10 percent of the bone marrow. Smoldering myeloma aims to keep it from becoming an active disease.

The current approach to treating smoldering myeloma is to “watch and wait.” However, Dr. Irene Ghobrial, medical oncologist at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, says waiting too long can produce active myeloma and serious symptoms.

Dr. Ghobrial tells SurvivorNet that some treatment options exist to help minimize the chances of smoldering myeloma from developing into full-blown myeloma.

Dr. Ghobrial uses treatments typically reserved for the first phase of active myeloma in patients with smoldering. “You can have a better survival with lenalidomide and [dexamethasone].” Those two drugs are part of first-line therapy for active multiple myeloma now being used against smoldering. Lenalidomide is a drug that prevents myeloma cells from processing proteins key to survival while activating the immune system. Dexamethasone is a steroid drug that can help reduce inflammation and pain while also killing myeloma cells when given in high doses.

Ghobrial also points to a monoclonal antibody, Elotuzumab (Empliciti).

“We added an antibody that activates the immune system, something called elotuzumab.” Elotuzumab is an antibody, a protein, that binds to a receptor expressed on myeloma cells. By “tagging” myeloma cells with this protein, the drug makes the cells easily visible to immune cells that can target and kill them.

What Goes Into Bone Marrow Transplants

“A bone marrow transplant is a therapy where your bone marrow and your blood cells are completely replaced by someone else’s bone marrow cells and blood cells,” Dr. Jun Choi, a hematologist-oncologist at NYU Langone’s Perlmutter Cancer Center, explains to SurvivorNet.

“In order to do that, you have to be fit and relatively young,” Dr. Choi adds.

Items to Consider Before Finding the ‘Perfect Match’:

- Patients over the age of 70 may be ineligible for a transplant. However, being otherwise healthy and having decent physical functioning is more important than age.

- Liver disease, heart conditions, or kidney disease can make it dangerous to receive a transplant.

What Happens During a Bone Marrow Transplant:

- Patients are given a high dose of chemotherapy “to kill all your blood cells and bone marrow cells.”

Dr. Javier Pinilla, head of the Lymphoma Section at Moffitt Cancer Center, tells SurvivorNet that because patients receive such a high dosage of chemo, they may experience serious side effects from low blood count to infections. For this reason, patients are usually hospitalized for a couple of weeks.

- New healthy cells are infused to replace the damaged cells wiped out by the chemotherapy. A central line (or central venous catheter) completes the infusion. It’s like a peripheral intravenous (IV) line but is typically much longer than a regular IV and goes up to a vein near or inside the heart. The transplanted donor stem cell will enter the body through the blood and grow into healthy new blood cells. You will be awake the entire time, and the process is not painful.

- The new healthy cells also create a new immune system, which will continue to surveil your body for signs of cancer and kill it at an early stage. During recovery, your cells start to engraft or grow and make new blood cells. It usually takes 2 to 6 weeks to begin seeing normal blood counts. During the first few weeks, while you are in the hospital, the transplant team will visit you regularly and watch closely for the following side effects of stem cell transplantation.

“This is a relatively intense therapy, and you need to be pretty strong to tolerate this,” says Dr. Choi.

After the procedure, patients will be immunocompromised for at least the first six weeks. Patients are at high risk of getting severe infections during this critical period.

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.