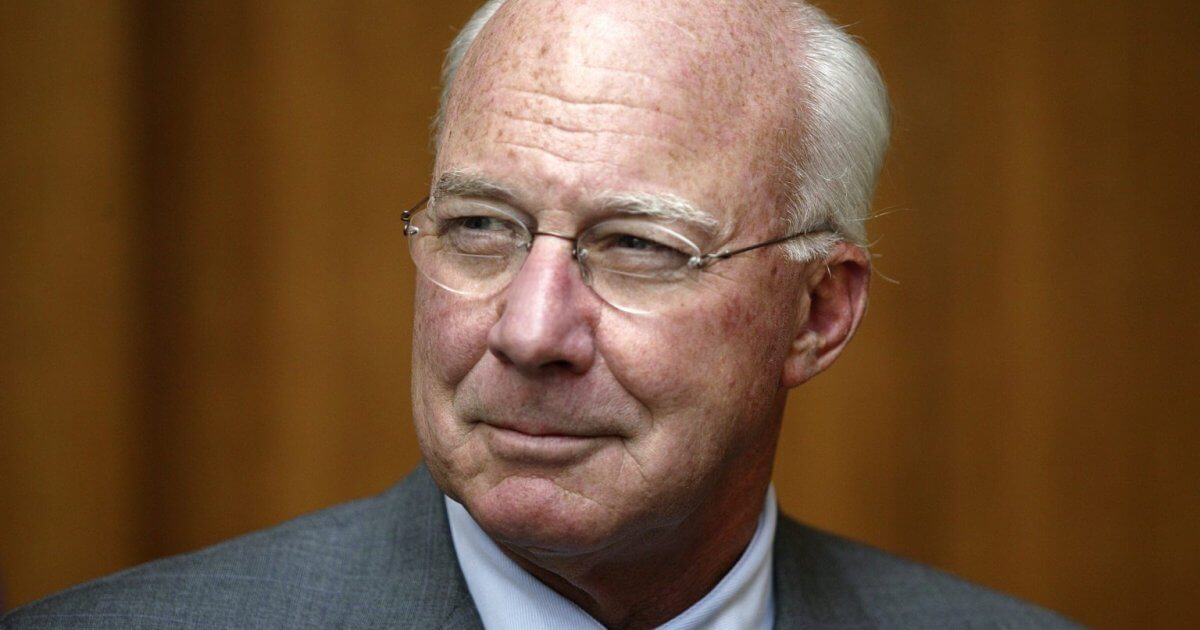

Mike Armstrong is a fighter, and few battles exemplify that more than his fight with leukemia, which was diagnosed two years into the disease. At the same time, he was fighting brachial plexus neuritis, an uncommon lung disease.

“It basically kills the nerve strands that go from the brain to the operation of the lungs,” Armstrong explains. “And with the strands dead, the only thing that enabled me to breathe and stay alive was my stomach muscles and my rib muscles. So here I was, battling a very bad metastasizing cancer, and I only had 20% lung capacity. ”

Read More

What led you to write Cancer with Hope?

To be perfectly honest, it comes down to just one word and cancer patients experience this word to a terrific degree, uncertainty. We’ve got a lot of challenges as we go our way in life, particularly in the market system of America. We’ve got education to deal with, we’ve got careers to deal with, family and compensation and healthcare and elections and it goes on and on. And many of these things can be of different importance and at different times. But none of them come close with the impact of cancer. It, of course, will kill you. And this uncertainty has to not only be realistically dealt with, it has to be overcome with much internal determination and spirit of hope.

Can you tell readers what they can expect from this book?

Well, the reason for the title was truly the reason for the book. Cancer With Hope. I mean we all know that cancer is life-threatening and it is so depressing and it is so often terminal. And it has not yet learned how to be cured. Thus, I wanted this book to communicate that there are a lot of tough complications that go along with cancer. But the thing that could never waver, that could never be a variable, is your absolute commitment, a lack of denial and the mindset to have hope. That’s why.

Can you tell us a little bit about your leukemia journey? How did you feel when you were diagnosed?

Well my leukemia journey was unique to cancer patients because three weeks before I got the phone call that I had leukemia, I had started a new job in California as the CEO and chairman of Hughes Space and Electronics. It was a wonderful job. And I had moved to Los Angeles. I had a new home. It was on the 17th floor of a hotel and I had a suite up there and I was going to shop for a house for my wife and I.

“My physicals each year, all had missed declining blood counts.”

Having moved a few times we thought we had it down, I go off to the job and do my best and my wife would get my kids all in order and wrap things up and sell the house and we would move. So we were doing all that. But the leukemia was in its third year. And my medical systems that I had taken, my physicals each year, all had missed declining blood counts.

What advice would you give to someone who has just received a cancer diagnosis?

Cancer is a unique disease. And I don’t think there’s any disease that anybody can cite that has more variations. You get the cancer of everything, nothing in your body that you can’t get the cancer of. And the kind of cancer can be one of three or four or five different cancers. Same name but it’s really not the same. The word cancer is common because the genetics of the disease are common across all the other differentials.

“I submit to you that with a little more homework you’ll find that most cancers can be beaten.”

But my advice to new cancer patients: Your first understanding is it can be fatal. I submit to you that with a little more homework you’ll find that most cancers can be beaten. Some can only be beaten for some years and some can be beaten for the rest of your life. But you never, never want to say “never.” You always want to strive for being in the bucket that survives however long that may turn out to be. And so the only recommendation in your environment is work to get the very best doctors who have successfully treated your cancer. They will be the background and the reason if you do in fact live.

How did your time as the chairman of the Board of Trustees at Johns Hopkins inform your own medical journey?

And by having that experience ahead of time at Hopkins, I had some insight. Not because I experienced it, but because others around me did. And I learned from them.

And the thing that I learned about that was so helpful, particularly in my very first cancer, was that I was not that familiar with medical trials. Drug trials. And as it turned out, since I had had that leukemia for two-plus years, it was very advanced. And the normal treatments, the doctors wouldn’t even discuss.

But they did know of a medical trial that was filling up with patients and there was only going to be 100 patients, there were 99 now so I would be the last one in. But they went on to explain all the wonderful ingredients of this medicine. And why they had selected, for my very unique cancer. And it wasn’t unique because it was called hairy cell leukemia, a lot of people get hairy cell leukemia. What was unique about me is that they had never seen somebody who had gone undiagnosed for two and a half years with leukemia.

As a dad, what was the process like of telling your children that you had been diagnosed with cancer?

Three weeks in as the new CEO of a very large and very well run and very important company. And I got advanced cancer. And so I needed their help. I needed their support. And I had to kee p it secret. If it got out, can you imagine all the fun The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal would’ve had on this new CEO that they just wrote up? And the company and he didn’t even know he had advanced cancer and had had it for two and a half years? It would’ve been a terrible story.

“When you have cancer, it’s often very helpful and of tremendous relief to talk to people about it.”

And so it was so important I didn’t tell my children. I didn’t tell their spouses. I didn’t tell anybody. My wife knew it, my doctor in the Los Angeles Cancer Center knew it, and I took it to the GM board and the Hughes board. Those are the only people who knew it. And that was really the right thing for Hughes. The right thing for GM. It was a tough thing for me. Because when you have cancer, it’s often very helpful and of tremendous relief to talk to people about it.

You've had an incredible and very successful career what in your career are you most proud of?

I know this may not sound as important as it was, is, but the thing that I’m most proud of is starting my career. Because back in 1961 I was graduating, and I had signed up for at least six or seven companies who were coming to campus to interview them and hopefully spark some interest. And then one of the worst recessions in America’s history took place. All of the companies canceled their interview. So here I am, I’ve got a diploma, I’ve got one suit and I’ve got debt. Now, no job. No interview.

Hughes went on to become a leading professional at IBM, after landing a job in their Ohio office out of college.

What did surviving cancer teach you about yourself?

Okay. Well at the first cancer (leukemia), after the 30 days on the clinical trial, as I told you, at midnight I had a recurrence and I had to go back to the hospital and they put me in the intensive care ward and they locked the door and the only people who could come in there, my wife was not allowed to come in, were the nurses and the doctors. And so I was in a battle. And it wasn’t a battle of getting a better test score, it was a battle that my body had no immune system. It had an infection, and I was getting shots. And would those shots and my determination overcome my sickness?

“I think about how important that determination was to never give up.”

After three days, they expected I would show improvement. After three days I had shown no improvement. I was still sick. I still had a fever. On the fourth day, my fever turned around and it started to stabilize. And five days after that, I left the hospital. And so when I think about experiences, and I think about how important that determination was to never give up, when after three days I hadn’t risen to the expectation of the medicine or the doctors, would I now die? And I didn’t know the answer.

Now if you can execute some damn good determination on that fourth day where the odds are that you’re probably going to die, that’s a good test.

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.