I am a sophomore undergraduate student at Yale University and had the privilege of hearing the story of Sona Kocinsky, a pediatric osteosarcoma survivor. Following conversations and interviews, I have reproduced her story in her own voice, writing as her in the first person and working closely with Sona to accurately represent her experience. I hope her story of bravery, resilience, and hope is one that transcends time as Sona inspires us to pick up our broken pieces and make them into something beautiful.

*********

This is not a story with a clear beginning or end.Like most stories, this one bleeds into the crevices, into every breath I take, into the minutes in the morning when the sun hits the lavender of my walls making them almost look white. This is a story that takes root, growing and shrinking in places you have never noticed, and one that I will begin to tell you from a soccer field.

A Pain Rooted in the Bone

At our last soccer practice before Thanksgiving break, we were practicing a 4-on-3 attack drill, where four attackers attempt to score on three defenders and a goalkeeper. I breezed past Emily, dribbling the ball in between her legs, and zig-zagged my way past the center line and into the penalty box. I could feel my shoulder aching with every step I took, but I passed the ball toward Claire who kicked an outside shot, the ball soaring past the goalie's outreached yellow gloves and hitting the upper right corner of the goal.

"That was a great pass!" Claire ran up behind me and patted me on the back. I flinched, almost doubling over in pain, my shoulder sending searing pricks up my arm.

"Oh, I didn't mean to I didn't know your pain was so bad," she said.

I grabbed my arm, "No, no it's fine. Don't worry about it." My left shoulder throbbed. Did it hurt this much now? I didn't even realize how bad it had become.

"Alright girls," my coach called. "You know what time it is. Give me 5 suicides across half-field with 10 push-ups at the centerline." I heard all of my teammates groan reluctantly.

"Did I stutter? Give me five, now." Coach Johnson shouted as we jogged to the end line. After the first lap, I dropped down on my knees and placed my palms on the rough grass. I leaned on my arms before my shoulder started searing in pain. You see, it's hard to describe a pain that seems rooted in the bone. As if my arm had forgotten what it was like without it and could no longer hold up any weight. My arms shuddered with the effort as my teammates finished their push-ups and started on the next laps. My eyes were spotty with tears, mouth grimaced I could barely breathe.

"Orthopedics," my father said when I got back home that day, my left arm almost immobilized, "We need to get this checked." November break seemed like a good time as it wouldn't interfere with my schoolwork, and the end of soccer season meant that my shoulder could rest for a bit before the winter track and field season started up.

Little did I know what the next year had in store for me.

How Could I Miss This?

November 21, 2019, was a cold day. My parents drove me to the orthopedics practicing room, where he pressed around the back of my left shoulder, circling out the scapula, or shoulder blade, a term I would soon become familiar with, and examined the area. My dad thought it was a rotator cuff injury, and I thought it might have been a bad muscle tear, but the doctor shook his head when we proposed these explanations. He pressed into my back as I winced. I think this could be very serious, the doctor said, there is a defined mass on your shoulder this could be a tumor. I'm going to schedule an MRI for you tomorrow.

I stared in the mirror in the room. An unmistakable bump the size of my hand rested on my shoulder. It might just be swelling from an injury, I thought, It's probably nothing.

How could I have missed this? I wondered staring at it after getting back home, It's so obvious.

I don't remember much from the MRI the next day, but I remember sitting in the general waiting room after the fact, staring at the creamy brown and dark yellow panels on the walls. I had started listening to Christmas music I was someone who began celebrating Christmas weeks in advance (a trait some people may find annoying), but when you're faced with a possibly terminal disease you need some type of positivity in your life.

The HGTV channel played faintly in the background as the doctors talked to my parents. Other patients stole glances at me, a scrawny 16-year-old sitting in the middle of the room. An ad played on the television. Someone coughed quietly before my parents walked toward me.

“So, the doctors showed us images of the MRI,” my mother said, kneeling in front of me. “There is a mass, Sona.” She reached for my hands. “It might be, she paused, It”

“It might be cancer,” my father filled in the silence.

I felt my gut drop in my stomach. Cancer? I couldn't control the tears that started streaming down my face as I collapsed to the ground, my parents crouching next to me. Cancer. I may have screamed. Cancer. The HGTV channel, the other patients all disappeared. I remember sitting on the floor of my car's backseat, hugging my legs to my chest, and rocking. This can't be happening to me. It just can't be.

Mariah Carey Was Right

Most of me didn't believe that it was cancer. There was a growth, but it could be benign. Or it could be another abnormality. I was 16, active, and healthy this is the type of story you read on the news. It doesn't really happen, not to people like me, right?

The week after, I drove to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), in New York, to meet an oncologist. I went in for my biopsy at five in the morning.

As I lay in the hospital bed, with my left shoulder cleaned and prepped, I chose a Christmas playlist to play in the background as I was wheeled into surgery.

I don’t want a lot for Christmas

Sitting under the harsh light of the surgery room. Mariah Carey was right. When your life hangs in the balance, you don't want a lot for Christmas. My classes, friends, the math test I was supposed to study for after the break seemed so far away, otherworldly even.

There is just one thing I need

A faint buzz of the lights chorused in the background. What did I care about anymore? It's probably nothing. Everything is fine.

I don’t care about the presents

Underneath the Christmas tree

The world seemed to converge and flex, the walls of the room growing closer. The ache in my shoulder started to fade, and the world turned fuzzy.

I just want…

Did He Just Say Yes?

My father was standing over me the next time I awoke. He held a little blue fan he had bought at the gift shop. My shoulder was wrapped in thick white bandages and my arm was in a sling. My head pounded, with every breath I took sending shudders of pain down my entire body. I opened my bleary eyes, Is it I couldn't finish the sentence. My chapped lips hung open. My father swallowed, moving closer.

“Is it cancer?” Some part of me didn't want to know.

I traced the slow tick of the clock mounted on the wall. The pause was deafening.

"Yes, yes it is." He reached for my hand. The pain radiating from my shoulder swelled. I felt his fingers close around mine. Yes.

Yes? Did he just say yes?

"They think it's either Ewing sarcoma or osteosarcoma."

Do I have cancer?

"Look Sona, we're going to get through this together…"

Did he say yes? His words muffled together.

"Like, bone cancer?" I croaked.

Yes, he said again. My shoulder throbbed, a heat traveling down to my feet. I thought about soccer practice. I thought about school. I thought about my plans for the track team season during the winter. I thought about my SAT and applying to college. I closed my eyes, the pain flaring and my head heavy against the pillow. I don't remember falling back asleep.

And at MSKCC, three weeks later, I started chemotherapy for osteosarcoma.

This Is It

I sat in the waiting room, my eyes tracing over the Christmas lights on the wall when a nurse came to my mom and me. She handed us a packet with color-coded boxes corresponding to different treatment days blue boxes meaning chemo and yellow meaning recovery. The packet was almost textbook thick. I stared at the words: Cisplatin, Doxorubicin, Dexrazoxane, HD Methotrexate, and then fluids and hydration. The plan was nine months at best. Two rounds of chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, then a surgery, and then four more cycles of chemotherapy to kill the remaining cancer. Then I'd be done… hopefully.

The nurse began to explain the side effects which seemed like a never-ending list: "Many people experience changes in diet and taste, feel nausea, tired, and weak. Mouth sores can also be a common occurrence." I reached for my mouth red welts, oozing puss, and rotting skin I shook my head to get the image out.

"There can also be higher risks of infection and bruising, but it's all detailed in the packet. Chemotherapy targets cells that are fast-growing. So, many people also lose their hair during the treatment process, but it will regrow after treatment." The nurse went on. She reached behind her and rolled over an IV pole with a dark blue handle and yellow accents.

"This is an IV pole that will hold the chemotherapy treatment. You'll also get fluids from here. It'll be a few bags of medications and nutrients that will pass through your body." She pointed to my upper right chest, right above my heart. "You have something called a double lumen port here. The surgeon put it in when you got your biopsy. This is what we will use to give you the chemotherapy."

She led my parents and me into the chemotherapy station and told me to lie down. I stared at the ceiling which was completely made of windows. The sky was a dark gray. The clouds were thick and looming, bristling at the coming of rain. The nurse practitioner handed me a small cup of pills, nausea medications, and heart-protective ones. I swallowed them as she prepared the chemotherapy bags.

Then it began. The nurse practitioner connected the port in my chest to the IV pole, two needles pricking my skin. A steady stream flowed from the clear bag of fluid, through the tubes, and into my body leaving a cold trail. I stared at the sky. I remembered the soccer games I had played underneath rainstorms, which would now be all the games I would miss and exhaled. This was it.

Things Keep Piling Up

During chemo and fluids, I would have to go to the bathroom almost every hour. At times, I couldn't walk because of the nausea and weakness. Some days I forgot what it felt like to walk unassisted. I was transported around the floor on a blue wheelchair, head leaning against my arms. At one point I found out that the chance of survival for patients with osteosarcoma was 70%. A 70% is worse than some of my lowest test grades, I thought. I would be so upset over an 85% on a chem test, but my chance of life is lower than that.

I watched my hair fall out when I showered. I vomited, got blisters on the bottoms of my feet, and was always cold. I was always a lean person, but as the months passed, I lost weight, almost to the point of needing a feeding tube. So, I made a list of foods I would eat with my parents. Buttered popcorn, spicy jalapeño chips anything that could cut through my destroyed taste buds made it on there.

And it was hard. There were always delays in the chemotherapy. My blood counts would be too low, I would get a fever, or I would have extreme side effects. Sometime in early 2020, an echogram found a blood clot near my heart, and they told me that I had to inject myself with blood thinners. Chemotherapy, anti-nausea medicine, fluids, week after week, and now I have to inject myself with blood thinners twice a day? It was small compared to everything else, but the things just kept piling up. I stared at the injection site in my arm, the skin sore and bruising. It just wasn't fair. I wanted to scream or run away, but I was too tired to even really be mad. I could feel these emotions building up in me but couldn't do anything about it. It was as if I was powerless against this tumor that had commandeered my life.

But I didn't go through this alone. Not by any means.

The day after they found my clot, a close family friend brought a bag of buttered popcorn my favorite food that she had popped, buttered, and salted herself. With every bite, I could feel the butter settling into my crevices and edges, smoothing them inch by inch. My grandparents would take me to chemotherapy, telling me stories on the car rides there and back. Every time I got back home after treatment, my sister would be waiting in the garage to carry the IV fluids backpack to which I was hooked up and would prepare a perfect place for me on the couch. My father when I had the energy would take me on walks around the treatment centers and help me do school work so I wouldn't fall behind. He would always put on a smile and say that everything was going to be alright and that it was going to work out. My mother never failed to remind me that it was okay to cry, that it was okay to be mad, that there were people behind me to be strong for me on the days that I myself couldn't. I met other cancer patients in the pediatric ward and watched them play games and laugh. Slowly, I began to see life in the nooks and crannies, existing within the cracks. During the times I could walk down the hallway by myself, in the flowers that began to bloom at the coming of spring, in the pages torn out from my chemotherapy schedule packet, the pages dwindling with every passing day.

It’s the Little Things

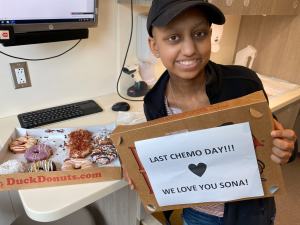

In December of 2020, I finished my last rounds of treatment and was officially cancer-free, a year after my diagnosis. It was Christmas season again, and the decorations at MSKCC were the same as last year, glittering in the bitter cold of winter in New York. But evidently, my life could never be the same.

An experience like this is humbling. Originally, you think: why me? But a lot of other people have been through experiences that are hard and traumatic. When you go through a traumatic experience yourself, you learn about the things that other people have gone through. And when they open up to you, you come to realize that everyone has to face challenges in their lives.

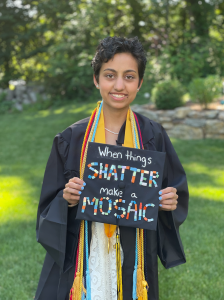

You can choose to go through it holding a grudge or being sad or depressed, and it's fine to feel that way sometimes, but I realized that I didn't want to go through life with that attitude. I wanted to go through it, continuing to live in the best ways that I could. I no longer play soccer or ride my bike as often, but I can go on runs around the neighborhood and find little paths in the forest with my sister. I can play tennis in a parking lot with my right arm and set up a badminton net in my backyard. Over the course of my treatment, I started painting again and building mosaics. Small things like that.

Chemo Curls

In my room, there are purple walls and a bulletin board with postcards showing pictures of Mount Rushmore, an Anastasia Broadway program, and lanyards from summer camps and sports teams. Interspersed between these mementos is a whiteboard with "Last Chemo Day" written on it by my sister, a sling for my left arm if it gets tired, and a little gold ribbon for pediatric cancer awareness.

This isn't a story that has a clean end. I go back for scans every few weeks; I sometimes forget that my left arm can't reach above my head, and my hair, once straight and long, is now curled. Chemo curls, they call it.

But still, I wake up every morning watching the sun stream through my window, and I look up at my wall where the newest installment has made its home.

Life isn't about waiting for the storm to pass. It's about learning to dance in the rain.

Sona is a rising freshman at Tufts University and is an osteosarcoma survivor since 2020. She has helped the Infinite Love for Kids Fighting Cancer organization by participating in a spin team during the Spin 4 Kids fundraiser, raising more than $12K. Her Make-A-Wish is to build a garden for a cancer center in Westchester that she went to during treatment, so patients can go outside while on fluids or treatment. I hear that they are building a mosaic mural of dandelions.

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.