Read More

- California’s Proposition 65 requires warning labels on anything that could contain cancer-causing chemicals

- Acrylamide is proven to cause cancer in rodents, but the FDA says there’s insufficient evidence to say the same for humans

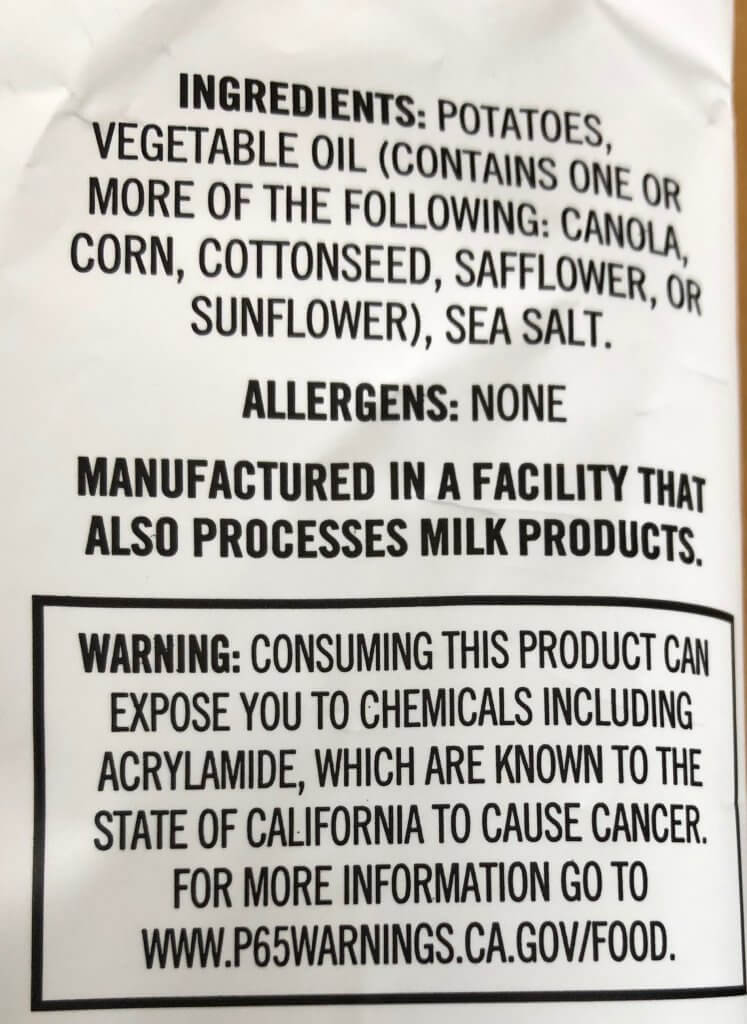

It's lunchtime here at SurvivorNet. We like to think of ourselves as a healthy bunch, but we do indulge in the occasional bag of potato chips (everything in moderation, right?) One of our favorite markets nearby carries a pretty standard, "Kettle-cooked-in-small-batches-and-seasoned-with-sea-salt" potato chip. This isn't the first time we've bought the chips with our (otherwise healthy) lunches. But it is the first time we've noticed something funky on their packaging. On the back of the one-ounce bag of chips, a bold warning reads, "Consuming this product can expose you to chemicals, including acrylamide, which are known to the state of California to cause cancer."

The curious warning label raised some questions. What is acrylamide? Does it really cause cancer? If it does, why is the State of California the only one to "know" it? Are we safe from cancer since we're eating the chips in New York? Should we stop eating them? I decided to investigate the curious case of the California-cancer-causing chips, and see for myself what the science says.

What is Acrylamide?

First thing's first, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defines acrylamide as "a chemical that can form in some foods during high-temperature cooking processes, such as frying, roasting, and baking."

(Makes sense; potato chips are fried, after all). A little more research taught me that it was 2002 when researchers first identified acrylamide in food. Since then, they've identified it in foods that are burnt or cooked at really high temperatures.

The FDA further explains that "acrylamide in food forms from sugars and an amino acid that are naturally present in food; it does not come from food packaging or the environment."

Is There Evidence That Acrylamide Causes Cancer?

In very high doses in rodents, yes. In humans, not so much.

Studies in the lab have shown that acrylamide causes lung tumors and promotes the spread of skin tumors in mice. In rats, they've caused thyroid tumors and uterine tumors, and the rat equivalent of breast cancer.

But the same has not been shown in humansand in 2015, a big review of all the research on acrylamide in humans published in the journal Nutrition and Cancer concluded that there was no evidence to show that dietary acrylamide (that is, eating acrylamide-containing foods) could cause cancer in humans.

The World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) lists acrylamide as a "probable human carcinogen" based on the rodent studies ("carcinogen" means something that causes cancer), but again, they don't have the proof to show it in humans.

The U.S. National Toxicology Program, the FDA, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the European Food Safety Authority all acknowledge the lack of evidence and need for further research, too. They call acrylamide a "likely carcinogen" or an "anticipated carcinogen," but none of the big regulatory bodies or health authorities have it listed as a known carcinogen.

Why is California the Outlier Here?

Enter "Prop 65." The State of California's "Proposition 65," technically called the

Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act, was first enacted in 1986. It requires businesses to inform Californians about exposure to chemicals "known to cause cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm." Under Proposition 65, anything that may contain one of a long list of chemicals (of which there are approximately 900) needs one of these warnings.

In a 2005 report, California's Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment explained its reason for including acrylamide on its "known to cause cancer" list.

"The ability of acrylamide to produce cancer in animals, and the applicability of animal findings to humans is well recognized by scientists in the United States and throughout the world," the OEHHA's report says.

But in the medical communityespecially in oncology researchanimal studies are seen as a starting point; seldom are results gleaned from mice and rats viewed as evidence that the same results would happen in humans. Research in humans is needed for that.

California's approach to defending the warnings, though, is that Californians have the right to know about the potential danger. Prop 65's tagline is "your right to know!"

Do Healthier Foods With Acrylamide Get an Exemption to Prop 65?

A few months ago, we reported that, after major pushback from the coffee industry, a California judge ruled that coffee did not need Prop 65 warnings about acrylamide and cancer. (Coffee beans are roasted at high temperatures, producing acrylamidesimilar to the way that frying potato chips produces acrylamide). The ruling was basically seen as a final verdict that coffee does not, in fact, “cause cancer” and that the health benefits of coffee outweighed the not-yet-proven-in-humans cancer risk.

RELATED: After Years Steeped in Controversy, The Verdict Is In: Coffee Does Not Cause Cancer

This same phenomenon happened in 2018 with whole-grain cereals; a bunch of cereal companies pushed back on the warnings (cereals are baked at high temperatures, too, and therefore contain low levels of acrylamide) and the courts ruled that the health benefits of whole-grain cereals outweighed the acrylamide. The courts also considered the fact that, in the rodent studies, the amount of acrylamide that caused cancer in rats was "the equivalent of a 150-pound person drinking over 11,000 cups of coffee per day," a chemist named James Coughlin told Discover Magazine.

Coffee and healthy cereal, accordingly, got a free pass on the warnings. Apparently, as evidenced by the snack we’re now cautiously crunching, potato chips did not.

Is There a Way to Minimize Acrylamide, Just in Case?

Again, it's not proven that acrylamide causes cancer in humansand California is using the animal link to mean it probably doesbut the FDA still offers suggestions for food consumers and manufacturers to limit acrylamide.

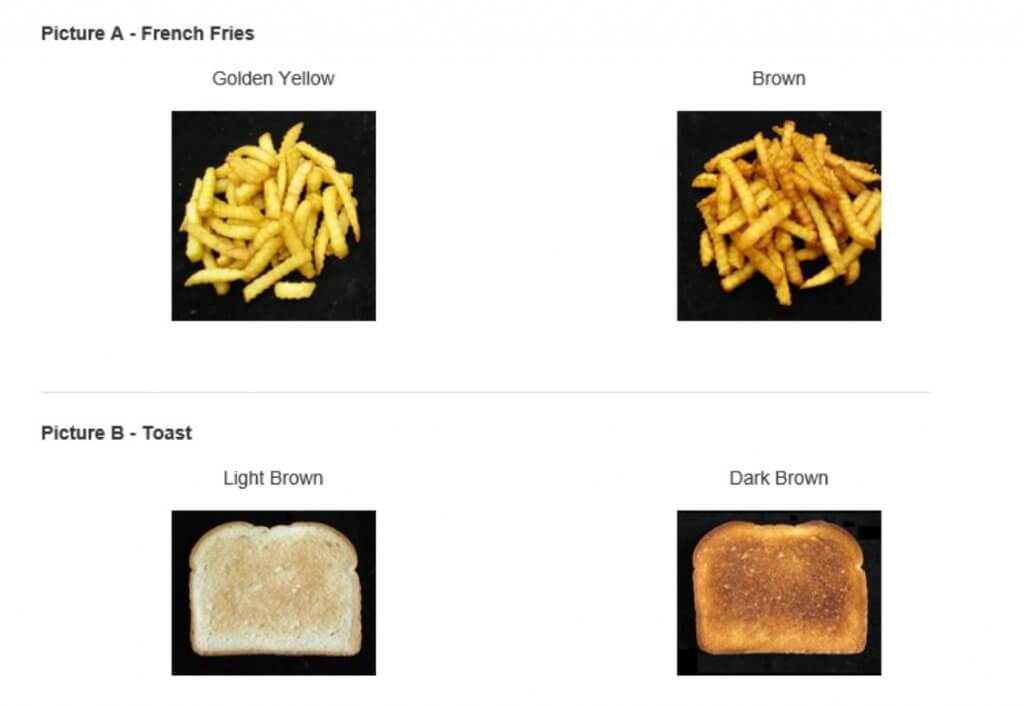

Soaking potato chips in water for about 30 minutes before frying or roasting them is one way to reduce acrylamide, for instance, as is baking or toasting food for a shorter amount of time. With toast, for instance, the FDA suggests keeping your toast to a golden brown color rather than a dark brown color.

All of this being said, the FDA's official stance on acrylamide and potato chips is that you should not cut fried, roasted, or baked potatoes out of your diet because of acrylamide.

"The FDA's best advice for acrylamide and eating is that consumers adopt a healthy eating plan that emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and fat-free or low-fat milk and milk products; includes lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, and nuts; and limits saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol, salt (sodium) and added sugars."

Learn more about SurvivorNet's rigorous medical review process.